For Example solo exhibition at BRIC

At BRIC, 647 Fulton St., Brooklyn, January 26-April 30, 2023.

Curated by Maria McCarthy

Exhibition text by curator Maria McCarthy

Exhibition on view: Jan. 26 - Apr. 30, 2023

ex·am·ple (n.)

from Latin exemplum

"a sample, specimen; image, portrait;

pattern, model, precedent;

a warning example,

one that serves as a warning,"

literally "that which is taken out”*

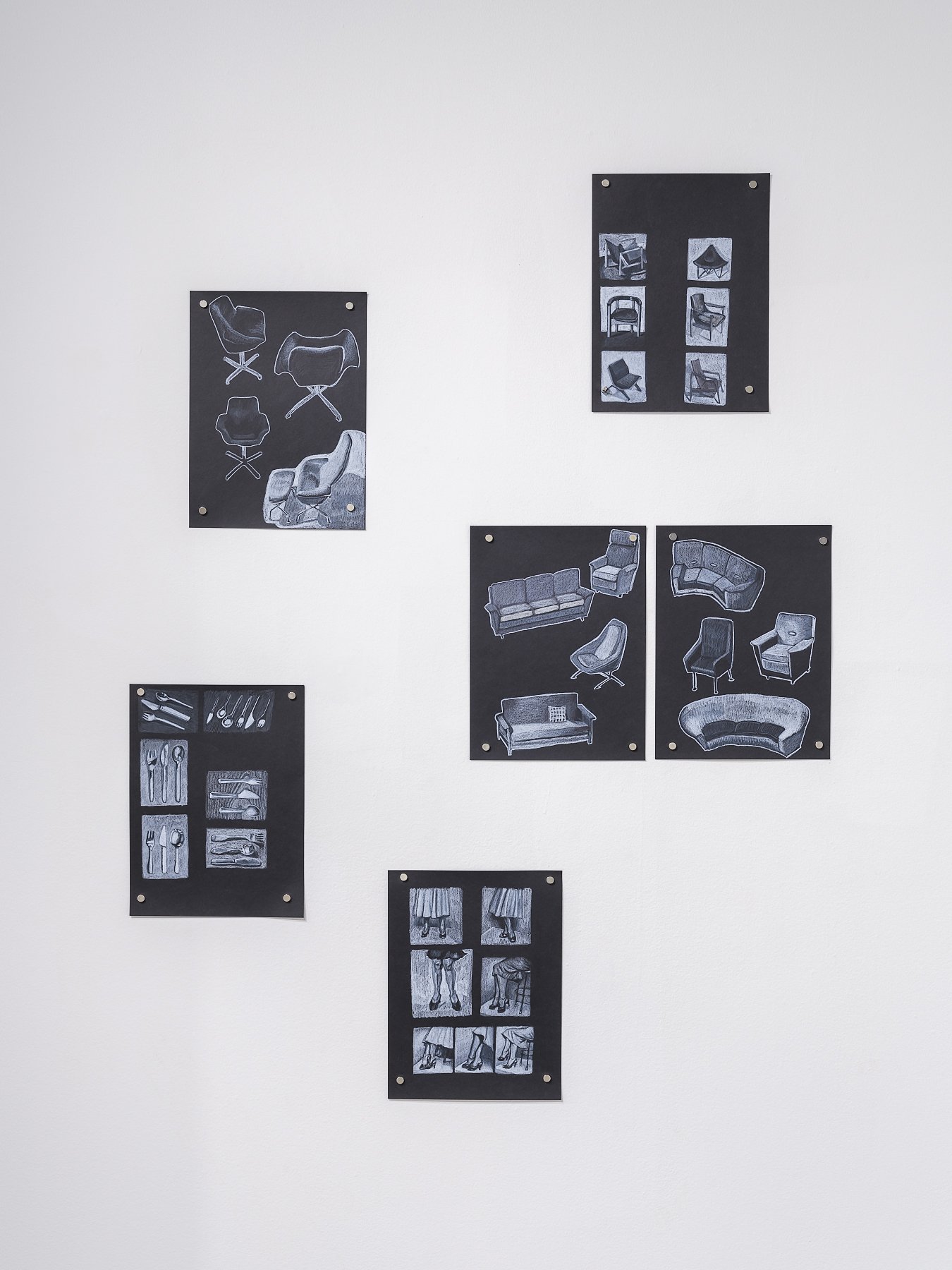

Featuring new work by 2021-22 BRIClab: Video Artist Buzz Slutzky, For Example presents the artist’s ongoing investigation into the relationship between mark- and meaning-making. Through drawing, painting, and film, Slutzky explores the aesthetics of authority, instruction, and knowledge production.

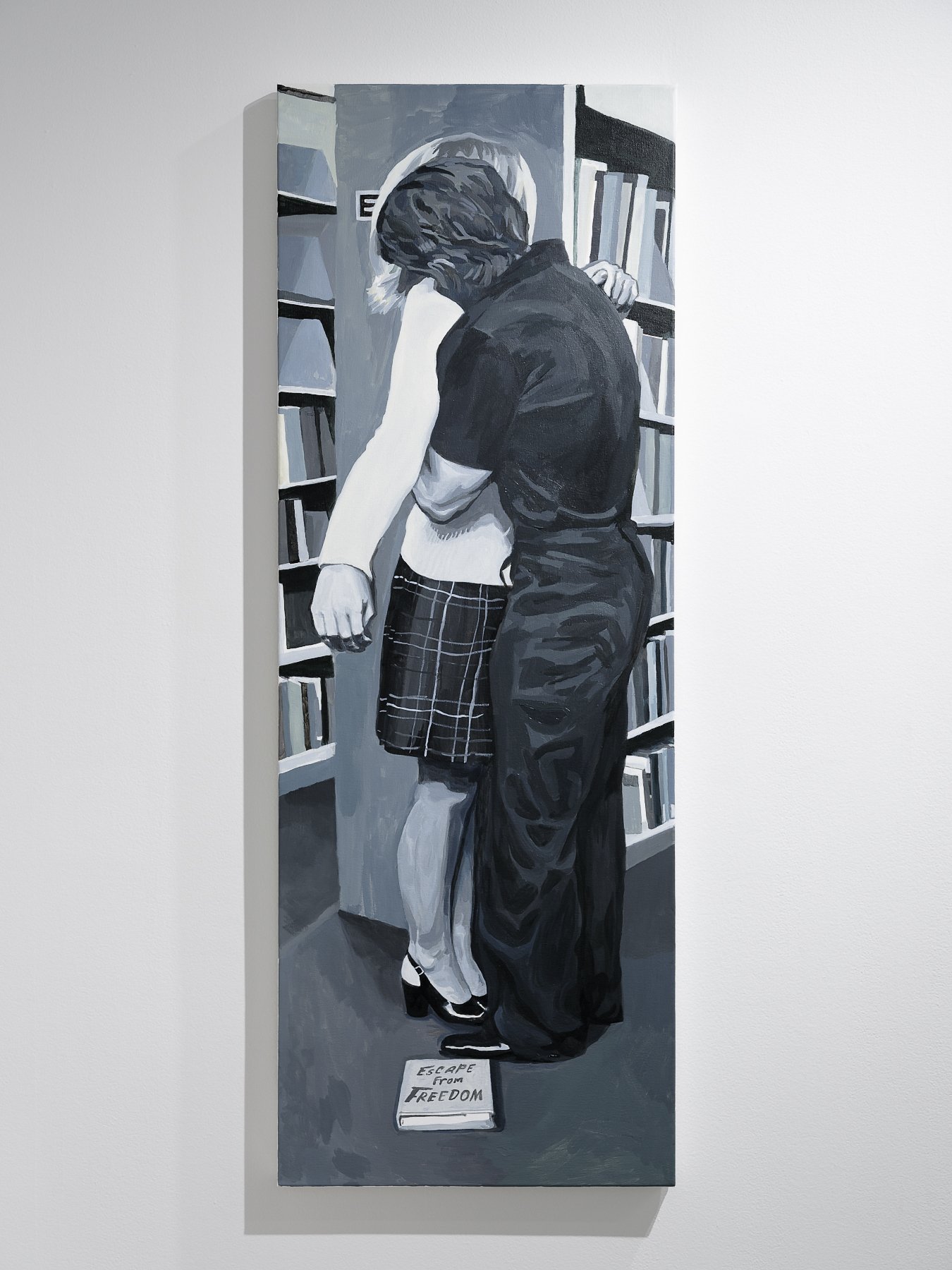

Slutzky’s interdisciplinary practice is, in many ways, an autobiographical and historical intervention. Slutzky creates drawings and paintings based on photographic images found in instructional manuals, visual arts textbooks, interior design catalogs, and family scrapbooks, many of which were published between the 1950s and 70s. Some of these books were passed down to the artist, like the 1977 self-defense manual, Looking Forward to Being Attacked: Self-Protection for Every Woman, originally purchased by the artist’s mother, and a sculpture textbook from the artist’s grandmother, Sylvia “Syb” Wolens, who was also an artist. Though these books were designed as tools for teaching, learning, and knowing, Slutzky pauses to ask: How does their meaning change when they change hands? This central question materializes in each stroke, smudge, and re-constructed scene, urging us to consider that there may be more to the story than the so-called ‘reality’ of a photograph.

Slutzky continues testing the malleability of meaning in their essay film, One Shorter than the Other, in which they share the story of their grandmother and her life as an artist, educator, and parent with a lifelong injury resulting from possible child abuse. As a collage of dreams, memories, and reflections, this visual retelling offers intuition as an alternative to what is inherited and what is imposed. Powered by the tension between what is buried and what is brought out by the passage of time, For Example challenges the enduring authoritative power of instructional images and inherited narratives.

For Example is organized by Maria McCarthy, Curatorial Associate. It is Slutzky’s first solo exhibition.

Exhibition page on BRIC’s site

Artist Statement for For Example

Around 2015, my mom, Alyson, was cleaning out her desk. She gave me this book, “Looking Forward to Being Attacked,” a self-defense manual for women from 1977. The book’s author, Tennessee Police Lieutenant Jim Bullard, created the book in hopes that women would approach moving through public space not in fear of being attacked, but looking forward to it: for with this manual, the reader would be fully prepared to defend herself against a stranger danger attacker. The photographs in the book show the specific body positions that people can use in the event of being bombarded by a man. My mom had bought it in earnest, but gave it to me knowing that I might be interested in it as an object. I tucked it into my studio books while packing for a residency, and began experimenting with drawing images from the book using a semi-translucent vellum and rubber tipped markers. Having done activist organizing around sexual assault prevention as a college student, my perspective was a bit different: that one would be generally more likely to be assaulted by someone they know, especially by a family member, than by a stranger. In looking at the photographs in the book, I noticed a strange tension between the man playing the attacker and his various scene partners– the women, not actors, were also not very committed to playing the role of a scared victim. Instead, they are often smiling at their pretend assailant, at times in a flirty glance, and seem to be enjoying his company. But the male actor is always committed to the seriousness of the operation. It made me think about the complexity of being in an abusive relationship, and how human relationships can contain such duality.

A few years later, when my parents were getting ready to sell their house, I was cleaning out books from my old bedroom, and found my grandma Syb’s 1952 sculpture textbook. I was struck that while this text was made over two decades earlier, there was something similar feeling– not just about the sense of light and tone in the printed image– but also regarding the sense of violence happening between the sculptors and their materials. Juxtaposed together, the images zeroed in on something I find hard to articulate: perhaps an unused bodily agency or manual power– the power of the hand to perform either acts of violence or acts of creation. And it also made me think about how creativity can be a tool to heal from trauma, which reminded me of my grandma’s story.

I knew on a certain level that my burgeoning body of work was tied up with my grandmother’s trauma and resilience. After seeing Laurie Anderson’s film Heart of a Dog (2015) in 2021, I began to see how my writing, drawings, archival footage, and other materials could come together to create an experimental essay film to bridge this body of work with my Grandma Syb’s story. It felt undeniable that working with her sculpture textbook had been a key to feeling like I was on the right track with my archival interventions, and I wanted a way to narrativize my questions around what impact her story might have had on me and my own art life. My essay film One Shorter Than The Other (2022) tells the story of my grandmother Sylvia, or “Syb”, and how she lived as an artist, educator, and parent with a lifelong injury resulting from possible child abuse. Because she had dementia from when I was about seven or eight until her death when I was a teenager, her story was a bit mysterious, and the idea of her overcoming possible abuse by making art made her into a kind of apocryphal art superhero.

Since 2015, I have been gleaning little free libraries, bookshops, and second hand websites for books that contain the type of photograph I like to render. A few different rules and parameters have emerged and made themselves known to me by repeating this process. Some commonalities have emerged in this archive of photographic texts: the photographs, which tend to be from roughly the 1950s to the late 1970s, usually portray hands doing things, contain a wide spectrum of light and values, emphasize the positioning of the body, and seem to imply instructionality, despite their arguable failure to do so. They advertise a way of doing things rather than a product, and emit a sense of unironic earnestness.

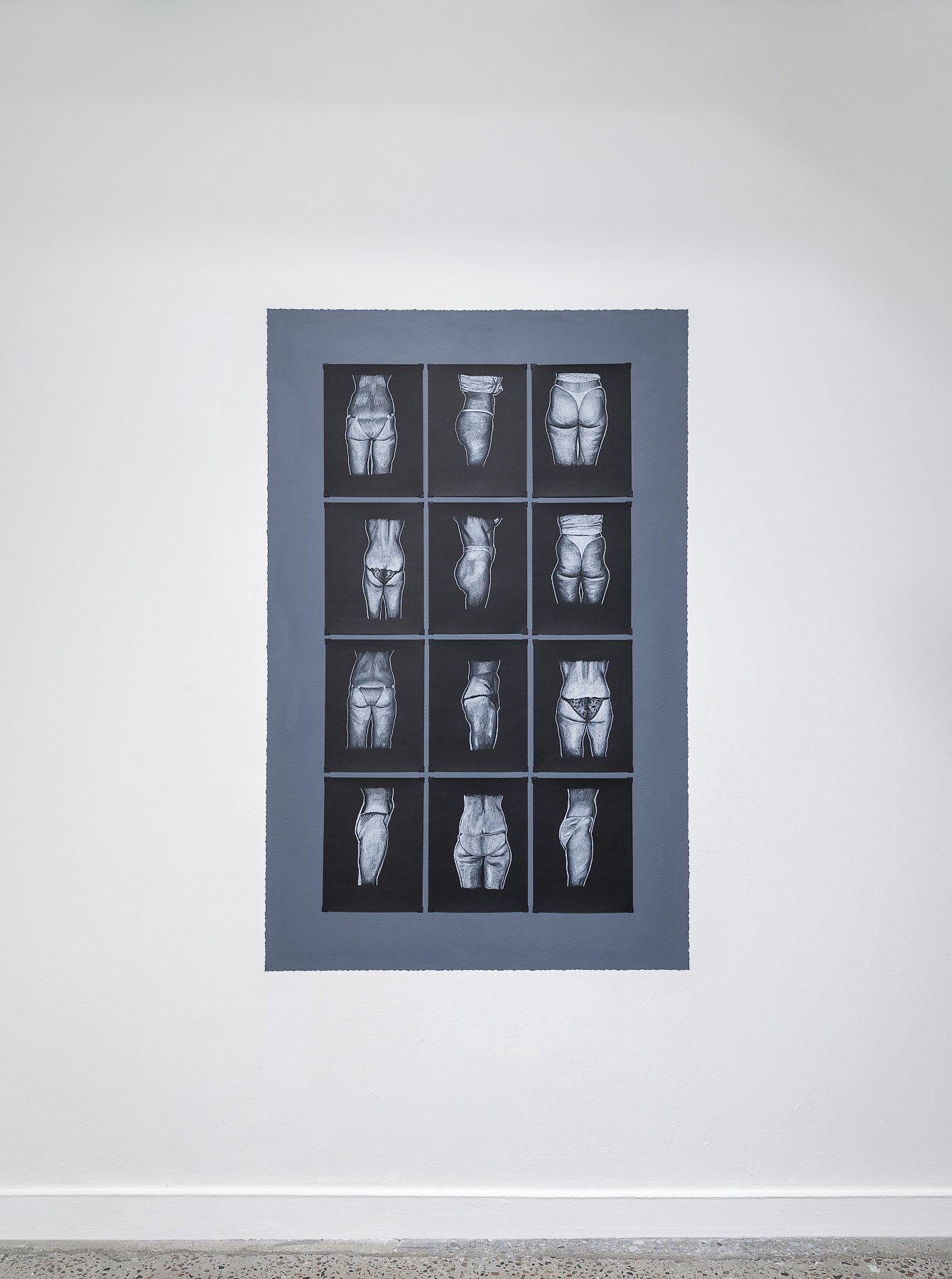

In 2022, I began working on black paper, building the greyscale up to white. I changed focus to drawing images from a workout manual, an interior design catalog, and a modeling handbook. I was conscious of choosing texts that related back to my relationship to my grandma, and her concern with attaining a certain level of womanhood through collecting objects, positioning her body, and styling herself. I started out studying the photographs of butts, and the ways that the bodies of participants in a workout class changed (or didn’t) throughout their exercise process; I was interested in how it appears that some of them are clenching their bodies to alter the effect of “before” and “after”, and how the viewer is expected to scrutinize these bodies in order to believe in the author’s authority. The images of furniture, upon finding them, struck me as spooky places where mid-century trauma may have occurred, or a place for a participant to position their body (presumably with their legs politely crossed).

My impulse to draw photographic images comes from an instinct to consume them by attempting to recapture the photograph’s sense of light and shadow, to study the range of values in the image, and to question how I would technically reproduce it through my own gestures. I remember hearing painter Nicole Eisenman talk about feeling like she has a little Dutch painter on her shoulder telling her which color to use; I relate to this intuitive process of moving up and down the grey scale of markers, pencils, and paints. I’m also inspired by Kerry James Marshall’s exploration of mixing color– how will each choice of tone and hue change the depiction of a photograph?

I want the image to exist outside of the context of the text or instructional manual that contains it, so that it can exist as an image outside of its role as a document, and I want to be the maker of a new archive transposing the images through my own hand. Just as the self-defense manual Looking Forward to Being Attacked feels cinematic in its creation of mini narratives, my process of culling an archive, remaking it, and editing it to emphasize a contrast between photographs feels akin to the process of film editing: through juxtaposing two images, a third meaning emerges for the viewer.